|

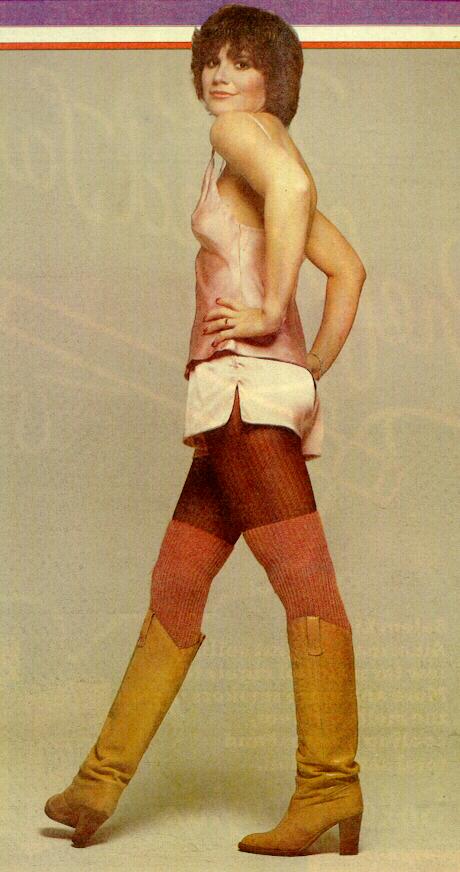

Nobody's perfect Linda Ronstadt strains herself Living in the U.S.A. Linda Ronstadt Asylum By Ken Emerson Living in the U.S.A. feels less like a record than it does a formal recital grimly intent upon establishing the versatility of its star. In nearly consummate command of her vocal powers, Linda Ronstadt sings more expertly than ever, but with a frown, knitting her brow in glum determination to hit and shade every note just right. She usually succeeds, yet because she seems to be judging rather than enjoying herself, the slightest flub sticks out like a sore thumb. If she would only relax, we could too. Instead, things are so solemn and strained that one winces (at least I do) when Ronstadt wobbles for even a second, as she does on a low note in the second refrain of Oscar Hammerstein and Sigmund Romberg's antique operetta tune, "When I Grow Too Old to Dream." In that song, Michael Mainieri's vibraphone is such an excellent foil that it's impossible not to notice the minute flaws in the singer's precious performance. Granted, such nit-picking would be out of order if Living in the U.S.A. were ordinary (or, for that matter, extraordinary) pop music. But pop music is about fun and feeling, while Ronstadt seems to be pursuing something entirely different and perhaps antipathetic: perfection. |

|

|

Because Living in the U.S.A. contains fewer new or unfamiliar songs than any of her

previous albums, it not only invites but demands incessant critical comparisons from even casual

listeners. Ronstadt's blandly beautiful rendition of the Miracles' "Ooh Baby Baby" is a case

in point. Here, the effort in her voice, the pinched strain at the top of her natural range,

reminds us of Smokey Robinson's delicious ease, Ronstadt's simple slurs of his shivering

glissandos, her stilted rhythm of his sexy, syncopating pause for a fraction of a second between

"baby"s on the last chorus.

Linda Ronstadt's concentration is so single-minded that she often misses entirely the wit and irony of her material. She roughens her voice to sing real rock & roll in Chuck Berry's "Back in the U.S.A.," but the original version was partly tongue in cheek, with a background chorus comically babbling, "Uh-uh-uh, oh oh!" (After all, when Berry recorded the tune in 1959, he had already done a stretch in reform school in the good ol' U.S.A.) Ronstadt, however, preoccupied with capturing the proper vocal inflections, reduces the song to punkish patriotism. In "Blowing Away," the singer's stentorian delivery willfully disregards the pathos of Eric Kaz' lyric. Though holding on stubbornly to the last syllable of the title line, then brutally cutting it off, creates a startling effect, such a technique defies the meaning of the words Ronstadt is mouthing. As unwavering as a rock, this woman will never be blown away, and her performance sounds coldblooded and infinitely less compelling than Bonnie Raitt's warm and touching treatment on Home Plate. The perversity of Linda Ronstadt's "Blowing Away" may have been prompted by the realization that, at the age of thirty-two, she's too established a star to evoke pity very easily. Ronstadt as much as admitted this by including Warren Zevon's sardonic "Poor Poor Pitiful Me" on her last LP, Simple Dreams. Indeed, the fascination of that record lay in its attempts to replace her no-longer-quite-credible persona as the little sex kitten with the big voice and the broken heart. On Simple Dreams, Ronstadt switched genders with liberated and liberating abandon, playing Mick Jagger one minute ("Tumbling Dice") and a cowboy the next ("Old Paint"); here a presumably male heroin addict ("Carmelita"'), there a traditionally lovelorn lass ("I Never Will Marry"). If she never settled on any one role, her brazen declaration of independence from sexual stereotypes unified the album. Living in the U.S.A., on the other hand, doesn't hang together. Sometimes it simply lapses into Linda's Lament, omitting, for example,the first verse of Elvis Presley's "Love Me Tender." Deprived of the line, "You have made my life complete" (and thus of any indication that the singer's love has been reciprocated), the song, kitsch to begin with, becomes an unbearably maudlin plea. Ronstadt sounds another unconvincing note of self-pity when she doctors a line in Warren Zevon's "Mohammed's Radio" (yes, she's now recorded four songs from his first Asylum LP) to read, "You know the sheriff's got his problems too/ And he will surely take them out on me and you." Zevon distanced himself from the "anger and resentment" he described flowing in the streets. For Ronstadt to include herself among the potential victims of police brutality is disingenuous. It's telling that the best performance on the new record is one in which the artist expresses pity not for herself but for another woman. "Alison" is an understated masterpiece that ranks with Linda Ronstadt's very finest work. Surprisingly, the reversal of the singer's gender does remarkably little violence to Elvis Costello's lyric. Instead, it's almost as if a sadder but wiser Ronstadt were addressing with wary tenderness and a stern, hard-won strength her earlier persona, regretting her victimization but refusing to indulge "the silly things" she said. And as Ronstadt argues with herself, her voice and David Sanborn's buzzy alto sax merge sympathetically, divide and commingle once more- mimicking each other in an intricate, eloquent pas de deux. Living in the U.S.A.'s other outstanding track is a stomping-mad rendition of "All That You Dream" that obliterates Little Feat's woozy original. The bluesy chromaticism of the melody is unprecedented for Ronstadt, who rises to- no, transcends- the occasion and becomes a dramatically different singer, one whose sultry sophistication suggests Maria Muldaur without Muldaur's fatal cuteness. Uncharacteristically unafraid to sound ugly here, Ronstadt angrily prolongs the final note of the last verse, hammering it into a violent yowl of protest against the dashing of her dreams. The passion in these two songs inspires the finest playing from Linda Ronstadt's band, which caresses "Alison" and bludgeons "All That You Dream." Otherwise, the musicians, like the singer, sound abstracted- stiff instead of rollicking, for instance, on Doris Troy's oldie, "Just One Look." Just as the listener searches in vain for the album's emotional core, they seem to be groping for its musical center. This is Ronstadt's first LP that has scarcely a trace of folk or country music. Though the latter does crop up on J.D. Souther's "White Rhythm & Blues," elsewhere Dan Dugmore plays pedal steel as if it were a synthesizer (and discovers some novel effects in the process). Pulling up roots is fine and dandy, but producer Peter Asher lays no new ones down, so Living in the U.S.A. jerks from cut to cut. Such discontinuity mirrors Ronstadt's dissociation from her material as she strains for the perfect performance. "My aim is true," she sings at the end of "Alison," and on this song at least, it is. Linda Ronstadt has hit many bull's-eyes in her career. The target, however, isn't Art with a capital A- it's the heart. |